“Broken soul meets broken heart for drinks and love on a waterbed of tears”

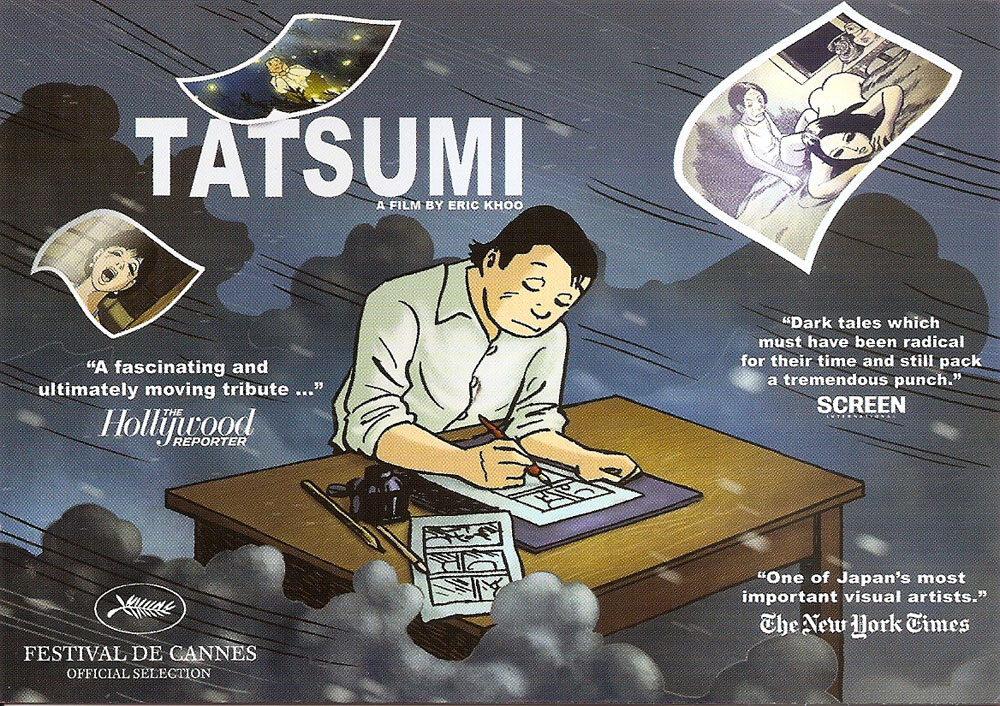

Tatsumi Film, by Eric Khoo, 2011

I am not a Japanese Animation buff. Yet, it was one of the blessings of my life to discover the genre, more or less by chance, while I was working for the Montreal Festival of Nouveau Cinéma during my twenties.

The magic of animation struck me as being simply limitless, inviting fantasy and surrealism, as well as straight storytelling, made of sober images drenched in humanity.

In my top 10 most loved films of all time is the desperately sad Anime, Grave of the Fireflies by Hotary No-Haka, about a brother and sister whose lives are torn apart by WWII. I watched it in the early noughties on my flatmate’s tiny CRT television. The image of the sky painted red with war was so powerful that I could have been watching it on just about anything and still cried my eyes out.

Years later, I attended the annual Japanese cinema programme at the ICA in London. I sat mesmerised by the animated film “Tatsumi A Drifting Life”, by Singaporean film director Eric Khoo, and based on the Manga autobiography of Japanese comics artist Yoshiro Tatsumi.

Tatsumi’s five short stories were narrated with such poetry that I was moved to scribble blindly, in the pitch dark of the theatre, the notes that would later turn into a song called “Grand Affair”.

I was watching “Just A Man”, the story of a middle-aged office worker stuck in a useless job in a grey city, living the invisible life of a forgotten soul. The man witnesses, in quiet desperation, the numb nightmare of his life.

On the verge of retirement, he becomes infatuated with a young, unattainable colleague of his. The man is stirred back to life and has an epiphany: he decides that, instead of letting his adulterous wife spend his pension, he will blow it all on a grand affair.

He makes his way to a brothel, where the prostitute he hires, is a teen who cries and eats all night, instead of having sex with him.

The next day, back at his desk, he miraculously connects with his beautiful young colleague, who has just had her heart broken. Her boyfriend is the company boss’s son; he won’t marry her because he’s been promised to another.

The man takes his angel out to dinner. All evening, they share their hearts with each other, and end up naked in a hotel room. Although full of fire and desire, the man fails to make love to the woman of his dreams, and the story reaches its pathetic conclusion.

…

I retell Tatsumi’s story of “Just a Man” in the song “Grand Affair”, a piece I’ve pulled out of my music production student archives (the male voice is mine, pitched down).

Grand Affair

Your colleagues despise you

You can’t trust your wife

She’s sleeping with your daughter’s man

You don’t even care

Living corpse seeks grand affair

You don’t even care

Living corpse seeks grand affair

Spinning legs and dancing tits

That hooker’s way too young

She won’t put out, you dry her tears

One more song unsung

Living corpse seeks grand affair

You don’t even care

Living corpse seeks grand affair

Until that angel from above

That goddess passed your desk

With only tender words she spoke

She brought you back from death

And you know she’s not for you

She’s lost her lover

And you know she’s not for you

Broken soul meets broken heart

For drinks

And love on a waterbed of tears

Love on a waterbed of tears